This builds up on my previous reflection, which provided examples of racist representations in children’s books.

Here, I want to provide some counter-examples, in order to show that it is indeed possible for a library such as the one I visited to renew its stock with an eye on diversity and empowerment. I believe it is important to raise awareness among teachers and parents and allow an open debate on what can and should be offered by a school library, given its educational purpose (in opposition, for example, to a private reading room). This is not a matter of political correctness but rather one of pedagogical ethics, which should also be based on considerations of age and critical development of the pupils.

It should be clear that racism (similarly to other -isms, such as sexism and ableism) is NOT a “personal” problem. It is wrong to dismiss it as a “subjective” issue. It is NOT subjective!It does not concern only the people who are negatively affected by it in their development and life choices. It concerns everybody, as it shapes our vision of the world and our understanding of power relationships within it. Therefore, prioritising diversity and empowerment is of paramount importance at all levels of school life.

What follows is not meant to be a list of specific suggestions but merely an exploration of books’ typologies, in order to show how books can be diversity oriented and inclusivewithout hints of “othering” or exoticisation. I have placed my focus mostly on Black characters and I have selected popular books (some of them available in many languages), but a selection of books to be purchased should consider diversity and inclusion in a much larger context.

Typology 1: Countering marginalisation

The most effective books promoting diversity and inclusion are the ones in which diversity is not thematised explicitly, but simply given for granted, by countering white (and male) normativity and depicting non-white characters in daily life and adventurous endeavours.

A lovely and funny book by a Japanese author, showing children how their body works in terms of sensorial experience.

Izzy Gizmo is an empowering book on determination. Izzy is a girl inventor who does not give up until she has achieved her purpose. Very empowering, not only for girls!

Princess Truly can solve all problems with her magical hair. Here, reversing usual tropes, a Black girl is the heroine protagonist, while the white girl is the secondary character in need of assistance.

Typology 2: Celebrating diversity

As well as making it ordinary, diversity needs to be explicitly “explained” and celebrated. Explaining diversity to children means placing it in context, both socially (what looks different in a context might be ordinary in another one) and historically (with honest accounts of what people make up our society and why).

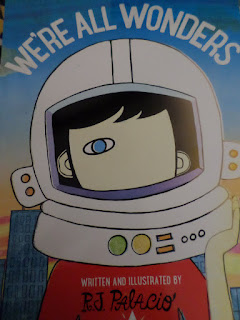

A wonderful story to thematise difference and acceptance with young children. It is a bestseller, available in all major languages.

(For older children, the corresponding novel: Wonder)

An inspiring celebration of diversity through the contribution of people of different backgrounds in different fields to the making of the USA.

Poet laureate Benjamin Zephaniah gives a voice to the children of Britain, showing that, no matter the background, a child is a child.

Focussing on the youngest child in the family, this lovely picture book from Madagascar shows how diverse families can be.

Typology 3: Providing role models

Inclusion of groups that have been traditionally marginalised and victimised also means that we have to “rediscover” and celebrate their history of resistance and their contribution to global culture.

“Black” is here a genre rather than a marker of identity. By the inclusion of white artists and by providing some background to their development, this book highlights the strong influence of Black culture (not only in terms of music but also in terms of Political Consciousness).

The collection of biographies “Little people, big dreams” is a great tool for children not only to be introduced to relevant historical figures but also to feel for themselves as children a sense of empowerment. In fact, these biographies focus in the first place on the historical character as a child. Away from the “victim role” and right into resilience and self-determination!

Typology 4: Giving a twist to a common topic

Another way of promoting diversity and respect is by reversing a common trope, thus having people look at things in a different way. This strategy involves giving a twist to a common topic or image, so that the power relations that usually come with it are put into question. This can be applied to any topic. Here, I provide the example of adoption, which is usually understood in terms of “first world - developing countries”, “white adopters - adoptees of colour”.

A girl finds a light skin baby abandoned in the bush. She takes the baby home to her already numerous family and finally persuades her mother to adopt her.

A white grandfather explains adoption to his grandson. The book presents and celebrates adoption as a traditional practice in many cultures across the world.

Typology 5: Overcoming stereotypes by spreading knowledge

Knowledge is the best weapon against prejudice. Therefore, we need books offering reliable and detailed knowledge about topics which are usually heavily loaded with stereotypes. Here, I provide the example of the African continent, whose plurality and complexity are seldom acknowledged.

Several African countries are presented (not all of them, because Africa is very big!) with beautiful pictures illustrating daily life. This is not about giraffes and lions nor about straw skirts. It is about children in urban as well as non-urban settings, about their daily habits, family life, traditions and play.

Realistic and respectful depictions.

Fashion, art, music, nature, architecture and many other subjects are presented in this book which tries to convey the diversity and richness of the African continent.

This book centres on one of the central figures of the oral tradition in the region of the Sahel. The role and functions of the griot are illustrated and explained in detail, with fascinating accounts of the Mandinka traditions.

Typology 6: Learning about other places and cultures though powerful (but reliable) stories

It is a fact that, when telling stories from elsewhere, most Western authors tend to reproduce (sometimes unconsciously, or willingly catering to a Western taste) stereotyped images that do not significantly add to our knowledge of the world. In the case of stories with an African setting, we are used to see exotic images of wild animals and rural villages in unspecified places. The following examples are meant to show how it all looks very different when the story is set in a specific location and present a realistic and respectful portrayal of its inhabitants (notice, for example, how, differently to what we are used to see, African authors have their characters dressed up according to the local code).

Congolese author and illustrator Dominique Mwankumi has many books set in specific setting, often providing, at the end of the book, several pages with information and pictures of the place in question.

Cameroonian author and illustrator Christian Epanya tells fascinating stories illustrating the local customs with richness of details. This story tells of how a boy from a Bozo village in Mali became a well-known photographer. All his stories are brilliant and teach us a great deal about real places in West Africa.

In the collection “Le caméléon vert” we find a variety of stories from different African countries.

Ghanaian author Meshack Asare revisits the richness of the ancient Ashanti philosophy conveyed by Adinkra symbols.

There are a number of very good comics from Africa. This one, about a little girl from the Ivory Coast, is suited for young children. By the same author, for older children, the best-seller Aya de Yopougon.

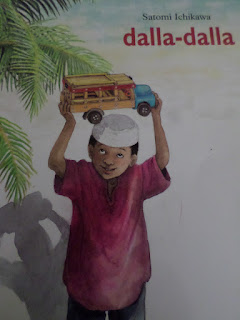

Japanese author Satomi Ichikawa has many of her stories set in Africa, with respectful portrayals of both places and people (even if with some exoticism).

Finally, a story from the Caribbean. In his stories, author Dany Laferrière revisits his childhood in Haiti. This one is about the “day of the dad”. A bit scary, but what a wonderful alternative to Halloween!

Typology 7: Revisiting the classics

Here I’m bringing together two different typologies. In the first place the re-visitation of stories which are familiar to all in Europe, by way of re-writing or re-illustrating. This strategy has readers look at classical narratives from a different point of view (an example would be the post-colonial rewriting of classics such as Robinson Crusoe from the point of view of the colonial subject). In the second place, the re-visitation of classics from elsewhere, for example the diverse oral traditions from the African continent. These are best presented in written form by local authors with knowledge of the original language and of the sophisticated meanings of the cultural specificities in question.

Rachel Isadora has re-told numerous well-known stories placing them in an African setting.

Stories from the oral tradition of the Sahel region re-told by a major author from Mali. As mentioned in my previous document, this is a viable and more appealing alternative to Western versions reproducing the colonial imagery.

The publisher Dodo Vole from Madagascar offers lovely bilingual books about local mythologies, having them illustrated by local children. At the end of each book one can find a picture of the children who participated in the project.

Typology 8: Creating bonds

While acknowledging and respecting differences among people and cultures across the world, a humanistic approach helps us create bonds across those differences and in spite of the distance. Using a humanistic approach in picking up books for our children means choosing stories that have a universal value beyond the specific cultural context in which they are placed. Stories about basic feelings such as love, fear, frustration, joy, etc. create bonds in that they show children what all human beings have in common (even if emotions may have different expressions across cultures).

An empowering story about a bright little boy who can defy fear with the force of love.

Please note that in my previous document I had contested another book by the same author for the racist iconography of its illustrations.

A philosophical exploration of the fundamental question: Where was I before I was born? With a focus on love and family bonds.

A lovely story from South Africa, about a boy and his grandmother and about a new pair of red tackies. A love-fraught depiction of the different rhythms of ageing and growing up.

Strategy 9: Promoting empowerment by addressing privilege and discrimination openly

As long as racism and other -isms are reduced to subjective issues rather than seen as unjust power structures to be dismantled ASAP, it will not be possible to fully empower anybody. Away from the hypocrisies of political correctness and from the racism inherent in a colour-blind approach, we should appreciate books which can find the right language to openly address privilege and discrimination with young children and teach them to recognise injustice and stand up against it.

There are many stories with Grace as protagonist.

In this particular story, Grace would like to play the role of Peter Pan in a school play, but one classmate tells her she can’t because she is a girl and another tells her that she can’t because she is Black. The story further shows the central role of empowerment (provided here by a supportive family, by a role model in the person of a successful Black ballet dancer, and by a fair teacher). In spite of the somehow sanitised version of reality, this book is very valuable and inspiring.

I’ve placed my focus on Africa and Black Diasporas (and partly on gender), but the same book typologies can apply to any marginalised group (take Native Americans, for example, given the appeal that the colonial iconography of the “Indian” has for children, or Romani people, who are the most discriminated group in Europe and appear in children’s books only in the very negative or exoticised figure of the “Gypsy”). Many good books are available from all over the world, which challenge the homogeneous, stereotyped and assimilationist views of the Western mainstream.